Hundreds of thousands of people line the streets of west London each year for Notting Hill Carnival – a flamboyant celebration of Caribbean culture.

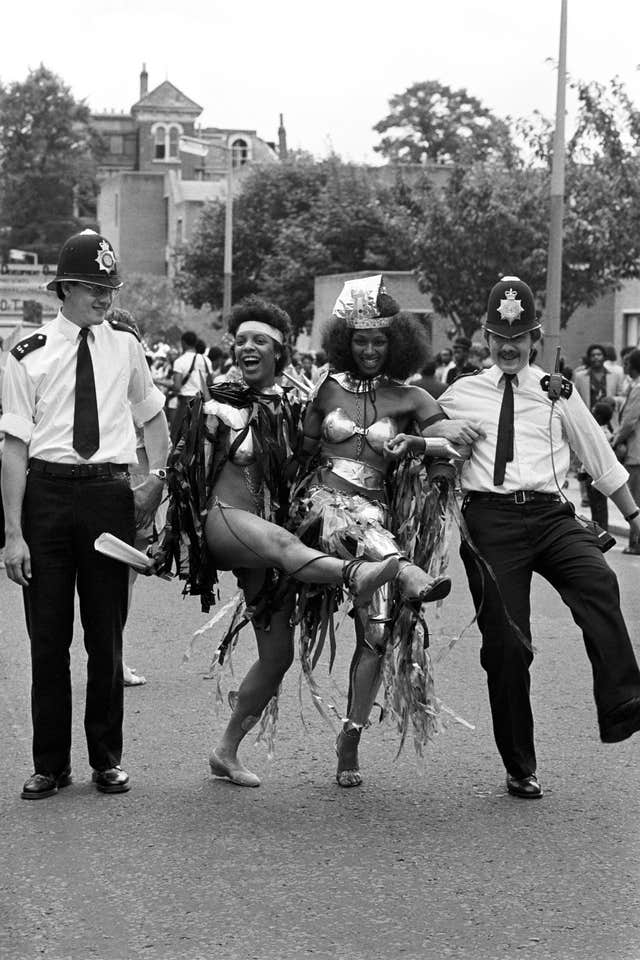

Celebrations include a parade of costumed performers dancing to traditional music reggae, calypso and rumba, with steel bands and sound systems stationed around the route.

Street food vendors sell a variety of fare including jerk chicken and fried plantain, which can be washed down with rum.

The festival opens early on Sunday with a J’ouvert celebration where revellers douse each other in paint, coloured powder and chocolate.

Spread over the August bank holiday weekend, the family event culminates with a main parade on Monday through the streets of W10.

Here are some of the key moments in the history of Notting Hill Carnival.

1959 – Claudia Jones, editor of Britain’s first black weekly newspaper, holds a Caribbean cabaret-style event at St Pancras Town Hall.

The gathering is seen as a rebuttal to race riots that had torn through the area a year earlier with white gangs attacking immigrants.

1966 – Social worker Rhuane Laslett is largely credited with organising the first bona fide carnival.

Crowds dance to steel bands and saxophones alongside horse-drawn floats as the parade gathers momentum.

She tells Time Out magazine her vision is to “take to the streets using song and dance to ventilate all the pent-up frustrations born out of the slum conditions”.

1970 – Police and black demonstrators clash after protests about police raids on the well-known Caribbean restaurant Mangrove, something of a hub for organisers.

1976 – Scores of people and officers are injured in running battles said to have started after police tried to arrest a pickpocket.

Violent scuffles between demonstrators and police last for several hours, with bottles and missiles thrown, windows smashed and fires lit.

Along with riots in Brixton and Toxteth that year, it leads to the implementation of the Race Relations Act 1976.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the area becomes increasingly wealthy and gentrified, moving further away from its run-down, tenement roots.

Attendance numbers swell and the West Indian-inspired celebration draws in more of the middle-classes and more diverse groups.

But despite the growing popularity, there are complaints about negative press coverage unfairly linking it to violence and crime.

2000 – Then-London mayor Ken Livingstone creates a carnival review group, leading to increased policing and safety measures, after the murder of two young men.

Fears are raised about the safety of the event and whether it should continue. More open locations are suggested as being more secure than Notting Hill’s narrow streets.

2016 – Facial recognition cameras are trialled to scan the faces of potential troublemakers.

Human rights group Liberty criticises the “intrusive” move and queries the transparency of the practice.

Festivities are marred by more than 400 arrests and four stabbings.

2017 – Celebrations are underpinned by a sombre tribute to victims of the fire at Grenfell Tower, just half a mile from the parade route.

Dozens of white doves are released, a minute’s silence is observed and the public are urged not to take photographs “at the site of our great loss”, something which has distressed locals.

The police are criticised by grime artist Stormzy for linking a series of drugs busts to the carnival on Twitter, when he asks: “How many drugs did you lot seize in the run up to Glastonbury or we only doing tweets like this for black events?”.

During the weekend, more than 300 arrests are made, and 28 officers are injured, with bottles thrown at them and blood spat at them.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article